Pole and polar

In geometry, the terms pole and polar are used to describe a point and a line that have a unique reciprocal relationship with respect to a given conic section. If the point lies on the conic section, its polar is the tangent line to the conic section at that point.

For a given circle, the operation of reciprocation in a circle corresponds to transforming each point in the plane into its polar line and each line in the plane into its pole.

Contents |

Special case of circles

The pole of a line L in a circle C is a point P that is the inversion in C of the point Q on L that is closest to the center of the circle. Conversely, the polar line (or polar) of a point P in a circle C is the line L such that its closest point Q to the circle is the inversion of P in C.

The relationship between poles and polars is reciprocal. Thus, if a point Q is on the polar line A of a point P, then the point P must lie on the polar line B of the point Q. The two polar lines A and B need not be parallel.

There is another description of the polar line of a point P in the case that it lies outside the circle C. In this case, there are two lines through P which are tangent to the circle, and the polar of P is the line joining the two points of tangency (not shown here). This shows that pole and polar line are concepts in the projective geometry of the plane and generalize with any nonsingular conic in the place of the circle C.

Reciprocation and projective duality

The concepts of a pole and its polar line were advanced in projective geometry. For instance, the polar line can be viewed as the set of projective harmonic conjugates of a given point, the pole, with respect to a conic. The operation of replacing every point by its polar and vice versa is sometimes known as reciprocation.

General conic sections

The concepts of pole, polar and reciprocation can be generalized from circles to other conic sections which are the ellipse, hyperbola and parabola. This generalization is possible because conic sections result from a reciprocation of a circle in another circle, and the properties involved, such as incidence and the cross-ratio, are preserved under all projective transformations.

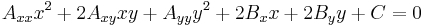

A general conic section may be written as a second-degree equation in the Cartesian coordinates (x, y) of the plane

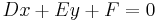

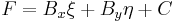

where Axx, Axy, Ayy, Bx, By, and C are the constants defining the equation. For such a conic section, the polar line to a given pole point (ξ, η) is defined by the equation

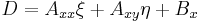

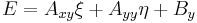

where D, E and F are likewise constants that depend on the pole coordinates (ξ, η)

If the pole lies on the conic section, its polar is tangent to the conic section. However, the pole need not lie on the conic section.

Properties

Poles and polars have several useful properties.

If a pole P1 lies on a line L2, then the pole P2 of the line likewise lies on the polar L1.

If a pole P1 moves along a line L2, its polar L1 rotates about the corresponding pole of the line P2, and vice versa.

If two tangent lines can be drawn from a pole to the conic section, then its polar passes through both tangent points.

Applications

Poles and polars were defined by Joseph Diaz Gergonne and play an important role in his solution of the problem of Apollonius.

In planar dynamics a pole is a center of rotation, the polar is the force line of action and the conic is the mass-inertia matrix.[1] The pole-polar relationship is used to define the Center of percussion of a planar rigid body. If the pole is the hinge point, then the polar is the percussion line of action as described in planar Screw theory.

See also

Bibliography

- Johnson RA (1960). Advanced Euclidean Geometry: An Elementary treatise on the geometry of the Triangle and the Circle. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 100–105.

- Coxeter HSM, Greitzer SL (1967). Geometry Revisited. Washington: MAA. pp. 132–136, 150. ISBN 978-0883856192.

- Gray J J (2007). Worlds Out of Nothing: A Course in the history of Geometry in the 19th century. London: Springer Verlag. pp. 21. ISBN 978-1-84628-632-2.

- Korn GA, Korn TM (1961). Mathematical Handbook for Scientists and Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. pp43–45. LCCN 59-14456. The paperback version published by Dover Publications has the ISBN 978-0-486-41147-7.

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0-14-011813-6.

References

External links

- Interactive animation with multiple poles and polars at Cut-the-Knot

- Interactive animation with one pole and its polar

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Polar" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Reciprocation" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Inversion pole" from MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Reciprocal curve" from MathWorld.

- Tutorial at Math-abundance